There is a cliché in popular music used to evoke the Far East flavor—Chinese, Japanese, Nipponese, you-name-it-ese.

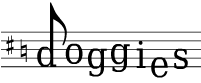

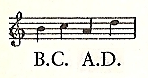

It goes like: “di di di di di, di, di, di, diii.” Click the score below to listen (or stop). Warning: Recorders!

The Oriental Melody dates as far back as the mid-1800s. Quartal parallel harmonies in a pentatonic key with a common rhythm that we all recognize no matter what variation.

The pentatonic scale is common to folk music around the world, but when it’s arranged in 4ths ([A, D] [G, C] [E,A]), the sound takes on an exotic Eastern characteristic. Here in America (and the rest of the west), we like our music harmonized in 5ths. Most chord progressions move in parallel perfect 5ths and most vocal harmonies are accomplished in major/minor 3rds, so it is unusual to hear lone quartal harmonies.

From novelty songs to cartoons, leitmotifs and modern pop, the many variations of the Oriental Melody share a common cadence, and when harmonized in fourths, you get instant noodles. Throw a gong in at the end, and now we’re talking Chinese.

Proverb: Like the fabled Chinese middle finger, the Oriental Melody can take many forms—the little or the middle or even the widdle.

Variations of the Oriental Melody:

“I’m Turning Japanese” by The Vapors (The intro is the same as the notation above transposed up a fourth.)

“Kung Fu Fighting” by Carl Douglas

“China Girl” by David Bowie

“Di Di Di Di Di Di Di I love You” by Los Doggies

Listen to “Cho Cho San” and fall in love all over again.

If you can think of any more, please put them in the comments below.