Much ado has been made in the media about Beyoncé’s lip-synched performance of the Star-Spangled Banner at the 2013 POTUS Inauguration, but in today’s perfectly pitched world, lip-synching is fairly common for these high profile events, and especially so for National Special Security Events.

The fan fallout today is not nearly as bad as say, America’s sickening realization that not only Milli, but Vanilli too, had been ‘lipping’ all along. Really, nobody believes that TV is real, but maybe the aesthetic illusion sort of conditions the audience to expect that something real is happening somewhere to create the illusion. Somewhere in the holographic universe, there really are rappers rapping that aren’t really holograms themselves, we like to believe.

Of course, there are artists today who still sing the Banner live, like Kelly Clarkson (luv u grl;), or The Fray who maybe could’ve used an auto-tuner on their guitar. It’s probable that the pre-recorded track Beyoncé used to lip-synch over was itself pre-auto-tuned and produced with all the nicenings and sweetenings of a modern recording studio, with digital tools that flatten out all the human flaw, and smear away all the imperfect goodness that is the human voice and soul.

It is befitting that Beyoncé lip-sang the Banner; the whole event is a farce. Everything about it is empty spectacle. The Inauguration is theater, like a movie theater, not like stage theater. What do people think this is, a 3-D IMAX showing of Les Miz (2012) where the actors really sing right there in the scene? Is it any surprise that human puppets prefer the voices of human robots?

Anyway, more interestingly for the purposes of this blog: whomever arranged this Banner decided to end it with a humorous musical cliché.

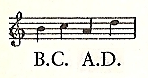

Beyoncé sings this Banner in E Major (the Banner traditionally is in the key of B-flat Major). The final cadence uses borrowed chords from E minor to create a harmonic progression that picardies from E minor to E Major. It’s called an Aeolian Cadence, because the borrowed chords belong to the Aeolian mode, or natural minor.

This cheeky little aeolian cadence is is a running musical joke among musicians, found in countless songs, can be tacked on to the end of anything, has been around for a few centuries, and is perfectly befitting Beyoncé’s bravado bravura and her bunk Banner.

The intention here was probably to go “big” or go home, like some studio executive kept telling the conductor to go “BIGGER!”, but in light of the the whole performance being revealed to be a sham, the intended epicness of the Aeolian Cadence comes off exactly as it should—ridiculous and regretful, heightening the pretense of the moment as only music can do for the theater.

Epilogue:

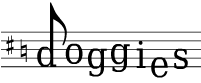

A few examples of the “bVI bVII I Aeolian Cadence”:

“With a Little Help From My Friends” by The Beatles (In the beginning and the end).

“Super Mario Bros. Ground Theme” by Koji Kondo (To the Bridge: dada da dada dada dada)

“Slave to the Traffic Light” by Phish (teased a few times during the middle and the end)

“Birth” by Focus (Wait for it…)

Can you think of other examples of this cadence? Please put them in the comments section below.

We made a little holiday video for the pagan Christmas carol classic “Big Surprise” from the movie

We made a little holiday video for the pagan Christmas carol classic “Big Surprise” from the movie

The Indian Chant originally comes from the Florida State University Seminoles 1960’s cheer “Massacre” played at football games by the Marching Chiefs.

The Indian Chant originally comes from the Florida State University Seminoles 1960’s cheer “Massacre” played at football games by the Marching Chiefs.