Is there anything sweeter than the atonal sound of your own name? Perhaps, maybe the lost melody of home?

Is there anything sweeter than the atonal sound of your own name? Perhaps, maybe the lost melody of home?

For those who’ve lived and lost, the memories and melodies of home stay with us, like an alpha earworm. If our names are sung (unless you speak a tonal language like Mandarin), the melody will sound sarcastic. For instance, a 2-syllable name that is sung with a rising first tone, and a falling second tone, let’s the person know they are being gently chided for their stupidity. However, there’s nothing but sine-wave sincerity in the forgotten bitones of telephone tonality.

In the age of landline phones, every home in America was denoted by a unique melody. If you got lost, or ran away, you could always echolocate your way back, like a homesick microbat. Now everything is on that fancy GPS, and cellular prerecorded music has eliminated the need for melodic home-association.

But I remember still—the memories and melodies of home. I hear it in my heart,

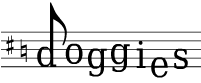

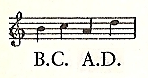

Don’t call that #, I don’t live there no more. This is about as close as it gets to speaking Chinese, or being a dolphin. Each number in the sequence is separated by 1/8 rests as the dialer’s finger moves between buttons. There is also a 1/4 rest in between the 3rd and 4th number, because that’s how we used to divide the telephone number’s seven note melody (notated as two measures of 4/4 above). The first 3 notes act like an antecedent, while the final 4 like a consequent. A birdy call and answer. A dueling guitar solo. I always liked the phone # above, and now it’s easy to see why. It resolves itself, beginning on the 4, and ending on the same number/chord. There is a rich metaphor somewhere in there, about musical resolution, nostalgia, and the ever changing technosoundcape, but fuck it, I’m no poet.

Go ahead and phone home to your home phone if you got one (or transpose your cell #). The bitonality of the telephone system makes for two melodies playing at the same time. The higher melody in D Major is the easiest to hear, while the lower melody in F Minor is more subconsciously felt (or ignored because of its dissonance).

There’s probably another metaphor in there about the retcons and confabulations of our subjective memories versus the objective reality of immediate experience, and how it relates to the two dissonant scales of telephone music sounding as one, but fuck dat.

Homey, homey; homé.

The television test screen, known as “bars and tones”, is used to calibrate color and sound on a TV screen or computer monitor. The accompanying tone—the soundtrack to this minimalist music video—is a high sharp B that stations use to tune TV’s. But at 1000 Hz, the bars-and-tones tone is a quarter-tone sharper than the closest B5 (987.77) tone. Much to the chagrin of couch-potato guitarists, the sharper tone certainly makes it difficult to tune along at home. Drag over the noteheads below to hear this sharpened B abomination that the reptilian broadcasters devised. Compare this false B to a real B5 below.

The television test screen, known as “bars and tones”, is used to calibrate color and sound on a TV screen or computer monitor. The accompanying tone—the soundtrack to this minimalist music video—is a high sharp B that stations use to tune TV’s. But at 1000 Hz, the bars-and-tones tone is a quarter-tone sharper than the closest B5 (987.77) tone. Much to the chagrin of couch-potato guitarists, the sharper tone certainly makes it difficult to tune along at home. Drag over the noteheads below to hear this sharpened B abomination that the reptilian broadcasters devised. Compare this false B to a real B5 below.  I remember an interview with Elliot Smith where he talked about watching a lot of TV while playing guitar to write songs, and I imagine it is a fairly common phenomenon for artists to work under distraction. The tube inside a television is said to emit alpha waves (among other things), that entrain your brain, lower your freqs., and put your mind at rest, so that you are an impressionable zombie ready to lap up the oozing TV set slime. Experienced mediators are said to be unhypnotizable. Perhaps, Elliot like many other stay-at-home singer-songwriters entered a meditative trance while zoning out in front of the TV, finger-plucking his guit-fiddle and whatnot, or like

I remember an interview with Elliot Smith where he talked about watching a lot of TV while playing guitar to write songs, and I imagine it is a fairly common phenomenon for artists to work under distraction. The tube inside a television is said to emit alpha waves (among other things), that entrain your brain, lower your freqs., and put your mind at rest, so that you are an impressionable zombie ready to lap up the oozing TV set slime. Experienced mediators are said to be unhypnotizable. Perhaps, Elliot like many other stay-at-home singer-songwriters entered a meditative trance while zoning out in front of the TV, finger-plucking his guit-fiddle and whatnot, or like

Real men know how to end a song. They don’t play chicken at the chorus, so why wimp out in the final bars? Real men kill their songs with their bare hands, like babies crying in their cribs far past bed time. Songs are the sons of men—prodigal, oedipal—and they’ll kill their composer daddies unless he kills them first. Real men hit it, then quit it, but they ain’t no quitters.

Real men know how to end a song. They don’t play chicken at the chorus, so why wimp out in the final bars? Real men kill their songs with their bare hands, like babies crying in their cribs far past bed time. Songs are the sons of men—prodigal, oedipal—and they’ll kill their composer daddies unless he kills them first. Real men hit it, then quit it, but they ain’t no quitters.