When you hear a high G, does it Stress Out your Shit?

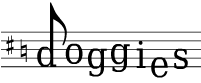

The international distress signal melody is a monotonal song in 7/8 time, written in the key of Morse Code, consisting of three quavers, followed by three crotchets, and another three quavers. Normally, the telegrapher is supposed to rest the equivalent note duration in between dits and dahs, but in an especially distressful signal, the beat is kept pulsing at the odd time of seven.

At a radio frequency of 500 kHz, the equivalent tone would be an high G7 (50175.4 Hz), an annoyingly high-pitched tone, and so is transposed down two octaves to a G5 in the widget above.

Here is a 45-second rock cover of “The SOS Song”. It is partly in free time to mimic the distress of a tattooing telegrapher, and features a 7/8 section as rescue efforts get mobilized. The choruses are rendered sailor-style, if not piratically derivative.

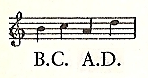

Morse code, like written music, is for the most part a dead language. While the commercial use of Morse code is just about obsolete, it is still a very powerful musical language that encodes simple rhythmic patterns into letters (and vice versa), and can be refashioned for much more esoteric forms of communication than relaying the massive bustling missives of business.

Tabla players, African Dummers, and other drumming cultures, speak in Percussionese dialects. However, rock drummers haven’t really much of a rhythmic vocabulary for their beats. We can refer to the style of the beats themselves―up-beat, down-beat, and possibly the African beat that they are based upon―the time signatures and tempos, and that vague quantifier of “feel”. We can speak in specifics―Dave Grohl flams and John Bonham triplets. But what if you were to describe a certain drum fill to someone? You’d be forced to dispense with all symbols, and just sing what it was you meant to say.

No longer friends. Now you can just say “Gimmie the D” in drumorse code.

Epilogue:

The Spring Peepers sing the same tone as the distress signal melody. Could they have provided the inspiration for SOS, in the way that the rhythms of the railways have been said to inspire Jazz beats?

The formula:

Frogs (G) + Railroads (Jazz) = Morse Code

Dah, Dah, Dah, Dit. Here’s some old timey porn.

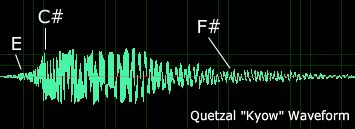

The singing stairs of the pyramid have lost some fidelity over the centuries, as the once smooth plaster finish erodes from each step, but one can still hear the famous echoes reflected back from hand claps, like the chirps of the Resplendent Quetzal, a bird who, according to Mayan legend, represents the plumed serpent Quetzlcoatl. The chirpy staircase of El Castillo is just one of many feats of “frozen music” (what Goethe called architecture) at the Mexican site of Chichen Itza, that honor the bird and her snake-bird god. During the Equinoxes, there is an undulating shadow display at the pyramid, like the scioform of the feathered deity himself, crawling up and down the limestone steps, the same spot from where his echoic voice chirps to the applause of pilgrims.

The singing stairs of the pyramid have lost some fidelity over the centuries, as the once smooth plaster finish erodes from each step, but one can still hear the famous echoes reflected back from hand claps, like the chirps of the Resplendent Quetzal, a bird who, according to Mayan legend, represents the plumed serpent Quetzlcoatl. The chirpy staircase of El Castillo is just one of many feats of “frozen music” (what Goethe called architecture) at the Mexican site of Chichen Itza, that honor the bird and her snake-bird god. During the Equinoxes, there is an undulating shadow display at the pyramid, like the scioform of the feathered deity himself, crawling up and down the limestone steps, the same spot from where his echoic voice chirps to the applause of pilgrims.

In the ancient world, the biggest noise polluters were the birds, insects, and weather. Humanity paid much greater attention to the sounds around her. Echoes were believed to be the voices of spirits by many ancient cultures, and the Resplendent Quetzal and her invisible song is still regarded as “the spirit of Maya”.

In the ancient world, the biggest noise polluters were the birds, insects, and weather. Humanity paid much greater attention to the sounds around her. Echoes were believed to be the voices of spirits by many ancient cultures, and the Resplendent Quetzal and her invisible song is still regarded as “the spirit of Maya”.