In our relentless pursuit of musical education, it is important that we frequently return to the source, and that is the tone at the beginning of all creation―the Om Tone.

This sacred syllable, discourse particle, wordless melody, or what have you, is said to be the background microwave radiation from the Big Bang, the tinnitus tones that ring endlessly in our heads, the buzzing of machines and insects, and the 1-note Song of the Universe. Whatever it is, humming this “aum” is good for you, as it allows for the free flow of Cerebrospinal Fluid―the elixir in which our nervous systems swim. Trying humming this low C at home now, and take it down as far as your throat length will allow.

In the beginning, there was the Tone, and the Tone was with Chord. For you see, every tone that you hear is made up of a ton of barley audible tones, called Overtones. These overtones form a little scale, which is the secret scale lying at the heart of all music.

Behold the Overtone Series, also known as the Harmonic Series. If you struck a low C on a piano, all of these other tones would sound as well, coloring the timbre of the piano.

Why are some chords pleasing and others not so? The Series is the key to unlocking the mysteries of music. Consonances are found between the tones at the beginning of the Harmonic Series, which are more audible than the dissonances, located at the end of the Series. In actuality, the Series keeps going for a while, with increasingly smaller intervals, less audible and more dissonant.

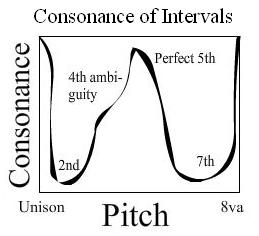

The tone, and its relation to other tones is called an Interval. In our western system of tuning, there are 12 intervals, just as there are 12 unique tones. Drag over the notes below, to hear each interval sound one by one. The idea behind breaking the 12 Intervals down into these categories of consonance and dissonance is borrowed from the book Twentieth-Century Harmony: Creative Aspects and Practice by Vincent Persichetti (not a book I’d recommend for introducing Music Theory).

The most consonant intervals are the unison and the octave as they feature the same tone. Tones right next to each other are the most dissonant when sounded together. This is the opposite of colors on a color wheel, where analogous colors when mixed produce consonances, and complimentary colors produce dissonances. But hey, let’s not get too lost in the synesthesia of it all!

The most consonant intervals are the unison and the octave as they feature the same tone. Tones right next to each other are the most dissonant when sounded together. This is the opposite of colors on a color wheel, where analogous colors when mixed produce consonances, and complimentary colors produce dissonances. But hey, let’s not get too lost in the synesthesia of it all!

Think of the above interval score like a bell curve (or maybe more like a sine wave), with the most consonant intervals in the middle―the perfect fourth and fifth―and the most dissonant intervals towards the ends.

This system for analyzing consonances can be applied to chords with more than two tones, to help us understand the subtle harmonies that makes us feel the way we do. Take your basic, garden-variety C Major chord. This chord is composed entirely of intervals located at the beginning of the Harmonic Series, making for a naturally pleasing harmony.

There’s nothing but consonances in this chord. It’s perfectly suitable for babies.

The guitar is designed to easily play these ‘Harmonic Series’ chords. They are called “bar chords” because of the bar-like finger-formation it requires to play them. This is how guitarists visualize their music.

The 5-line stave of traditional notation (see scores above) is traded out for a 6-line tab and finely mimics the vectors in a guitar’s design. Not only does the left to right movement show the linear flow of time, but it also represents the neck of a guitar as seen while playing it. The system of Musical Notation is more like a written language―which is to say arbitrary in its symbols―while Guitar Tablature is more like a drawing.

Notice that the C Major on guitar sounds a lot more dissonant than the piano version above. That’s cause of all the awesome distortion, which colors the timbre of the instrument, and makes for different overtones.

Thus, consonance is a product of many things, but mostly harmony and timbre. At which point, can timbre tip an ugly tone into consonance? When do the weight of dissonances bar any noticeable change in timbre?

There are other things too, less easily quantifiable, like context and attitude, that play their part. Why, just the “sexiness” of a lead vocalist alone can make you forgot all about dissonances.

Ya got questions? Crits? Write to us in the comments below.

Not all sounds are ear sounds. Some sounds are beyond ears, like head sounds. These sounds are known as tinnitus, and probably everybody experiences them at one time (as do our animal friends). You may temporarily hear a “ringing in your ears” after being exposed to triple forte rock music. These are just the “phantom frequencies” that are dying inside your brain, never to be heard again. Or you may be like me, and experience Chronic Tinnitus―a mildly annoying to deafeningly debilitating condition. Some sufferers have even cut off their own ears in the hopes of exorcising the sound. Of course, head sounds need to be decapitated. There have even been reports of objective tinnitus―nerve noise so loud that it can be heard outside of the head in which it is produced.

Not all sounds are ear sounds. Some sounds are beyond ears, like head sounds. These sounds are known as tinnitus, and probably everybody experiences them at one time (as do our animal friends). You may temporarily hear a “ringing in your ears” after being exposed to triple forte rock music. These are just the “phantom frequencies” that are dying inside your brain, never to be heard again. Or you may be like me, and experience Chronic Tinnitus―a mildly annoying to deafeningly debilitating condition. Some sufferers have even cut off their own ears in the hopes of exorcising the sound. Of course, head sounds need to be decapitated. There have even been reports of objective tinnitus―nerve noise so loud that it can be heard outside of the head in which it is produced.