Most pop music, and music in general, centers around a single note – the Tonic. In solfège, the tonic is called “doe, a deer”, as in “do-re-mi-fa-so-la-ti-do!”, or as musician’s like to call it “12345678!”.

The tonic is like the King of a Key. Everything centers around her. All other notes lead to her. That is why she’s also called The Root. Key changes are a way of usurping the king and replacing her with another; a new king and a new key. If the pervious key was well established, then the key change will provide a revolutionary rush in its first moments. After the new key is established, and the memory of the old key fades, then it must be time to change that key again. A song that is constantly changing keys as a principle embedded in its harmonic movement is known as a “Key Change Song”, or an “Endlessly-Modulating Joint”.

Before we hear a few examples of Key Change Songs, let’s look at the classic pop modulation. A fine example is found in the Big Bird tune Easy Goin’ Day. At 1:35 is when the key change occurs. After two verses and two choruses, the song jumps up a whole tone up from B-flat Major to C Major. This is the classic pop key change that drops hard at the very end of a song. The last chorus has a fresh face, like a brand new ruler put into power. But the new key change’s time is short, for the song promplty ends after one last modulatory hoorah. (Here’s the video link too, if the visuals don’t interfere with your ears.)

I’ve got a sweet tooth for Dolly. Check out her song Islands in the Stream with Kenny Rodgers. This song begins in C Major, plays itself out for a verse and chorus, then mysteriously jumps down six steps to Ab Major at 1:32. This seemingly downward modulation, actually pushes the melody lines up when Dolly takes over Kenny’s part. O to the MG! Does somebody want to do this song with me karaokely?

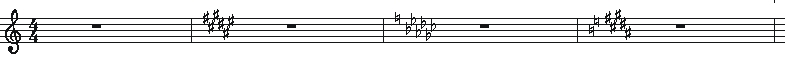

Those two songs above feature Key Changes as an exhilarating musical device, as a one time modulation, but what if the whole song is constantly modulating, as a feature of its harmonic movement? The song Ant by They Might Giants is one such song. This is a quintessential Key Change Song. With each verse, the song moves up a semitone. It begins on A Major, with the solo marimba, then jumps to Bb Major when the guitar enters (00:23), then up to B with the full band kicking in (00:46), and jumps up twice more to C(1:07) and finally C# Major for the very last verse (1:28). This song basically relies on an old folk trick, that says that if a song is going to have innumerable verses, that are basically the same, then it’s best to change key for each one, so they’ll each feel like they’re new. A semitonal modulation generates a lot of excitement, as two Keys a semitone away have the fewest notes in common of any major keys. For instance, in the song “Ant”, the A Major in the 1st verse has “A B C# D E F# G#” as its scale, and the second verse in Bb Major is “Bb C D Eb F G A”. That’s only two tones in common, the “D” and “A”, which makes the two keys fairly unrelated, and assertive of their own tonics (A and Bb, respectively). It’s like two Kings, with two completely different styles, vying for power.

Another Key Change song comes to us from the 1960’s, by duo Zager and Evans, with their apocalyptic one hit wonder In the Year 2525 (Exordium and Terminus). This song is a lot like “Ant” above. It changes keys with the passing of the years, following the same chord progression raised a semitone. In true 60’s fashion, the song fades out abruptly.

One more irresistible Key Change song is These Eyes by The Guess Who. Unlike the previous two examples, the onslaught of Key Changes comes at the choruses (“These eyes…”).

Wooh! That was the most loquacious post yet. There were more words than noteheads. And I don’t think I cursed once. Soon, they’ll have to start teaching this shit to kids.

If any of the above seemed of the over-yo-head variety, too esoteric and erudite, or just plain obssessive and nit-picky, might I refer the inquisitive reader to the mission statement of this blog. The purpose of these writings is to actually talk about the Music, which involves a written language that is as dead as Latin. Through the use of examples, sound widgets, and metaphors, I think the thrust of this or any post on this site can be gotten, gisted, or vaguely impressed upon any open mind out there. Y’know Beginner’s Mind?

Besides, Key Changes are felt deep down inside, in the cockles, in the penetralia, and only after they are felt do we bother to assign a little number or letter to them.

Peace out homeys!